More than 40 years ago, a small American independent film from a quirky character actor and French arthouse auteur revolutionized storytelling. With a middle finger pointed firmly in the direction of Sergei Eisenstein’s montage theory, My Dinner with Andre returned cinema to the more theatrical staging of the early silent film era. The catch? It’s pretty much all dialogue.

Today, My Dinner with Andre has become a cultural touchstone, perhaps more often referenced than actually viewed. Of course, The Simpsons did it. Perhaps better than anyone. Though Dan Harmon referenced it twice between Community and Rick & Morty. As did Frasier, Christopher Guest, and, coolest of all, Andy Kaufman. In some ways, it’s become the ultimate cultural signifier. You get the reference, even if you don’t get the film (or never even tried to in the first place).

More Like Why Dinner With Andre?

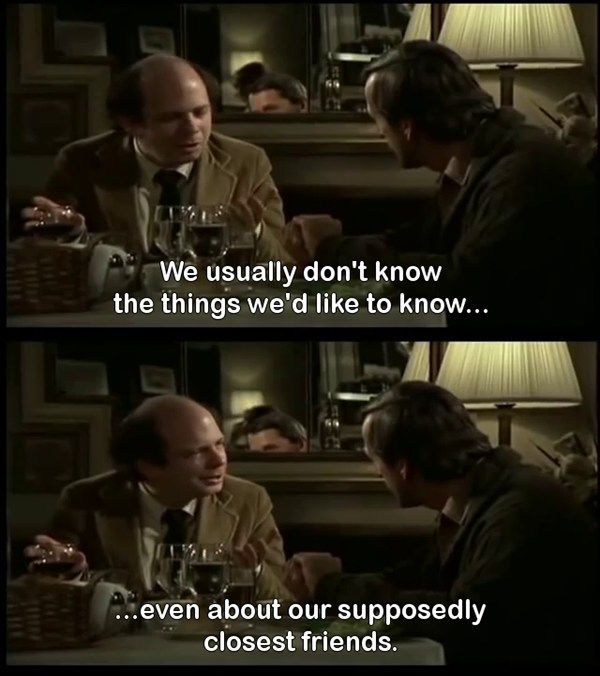

Beyond all the references, what makes My Dinner with Andre such a lasting film worth watching and rewatching? After all, it’s basically two privileged white New Yorkers talking for almost two hours. For starters, there’s the talking. This movie definitively proved that a movie could tell a story primarily through dialogue. Indeed, the central conflict of the film seems disarmingly simple: can these two somewhat estranged friends reconcile? At first, the divide between them seems merely spatial and temporal. They haven’t seen each other in a few years because Andre has been away.

Yet it evolves on a more complex, philosophical level. Andre is cultured and worldly; Wally is slovenly and insular. (Granted, his island is Manhattan). In a sense, it’s the same conflict between Plato and Aristotle that Raphael depicted in The School of Athens. Andre pushes for transcendent idealism filtered through post-hippie New Age adventures and theatrical occultism. On the other hand, Wally grounds both his pleasures and pains in the material world. As a playwright, his only concerns with theatricality revolve around how it pays the bills. By the end, the film becomes a reflection on storytelling itself, and the power to bridge divides. How does it achieve this?

We’re Not Bored Now

Although dialogue drives the action, the action still feels cinematic. In his exuberant review, Roger Ebert half-jokingly compared it to another classic film from the same year, Raiders of the Lost Ark. Filmmakers like Stephen Soderbergh and Quentin Tarantino have cited Spielberg’s action-packed adventure as one of the definitive works of film staging and shot composition. In fact, Soderbergh even recut a black-and-white silent movie version to appreciate this aspect. However, there’s a case that My Dinner with Andre is equally if not more masterful in the way Malle frames the blocking and the scenes. While a silent viewing would be an act of mindless contrarianism, pay attention to the different shot compositions, the edits, and the actions. In particular, the character of the Waiter, essentially extracted from a silent film with his visual cues.

Of course, there’s no movie without the dialogue. Again, apart from film hipster masochism, we don’t recommend the silent movie version of this.* Most films with conversational dialogue that feels natural and spontaneous often have a secret weapon: improvisation. However, in this film, it’s a magic trick. Wallace Shawn wrote the script, which he and Andre Gregory meticulously rehearsed and filmed. Yet Shawn took an improvisational approach to his writing, recording hours of conversation with Gregory and then reverse engineering the script from these. In fact, we could dub this whole process reverse improvisation. From a narrative perspective, it allowed for structure while also feeling loose and conversational. On the technical side, it kept this from being a nightmare for the editors and sound mixers.

The Beginning of the Rest of the Future Now

For young filmmakers, My Dinner with Andre shows how a basic premise with minimal locations and actors can succeed. Yes, there’s a reason why not many other films have emulated this style. For one thing, it’s hard. It takes two strong actors with good rapport, and a smart director up for a challenge. Still, we can all learn lessons from this film, whether it’s how to stage and cut a conversation or how to experiment in the writing process for a more natural style. At the very least, you’ll get all the reference on a more than superficial level.

Notes & Image Credits

*Which means Soderbergh will probably do something like it for his next experimental mash up.

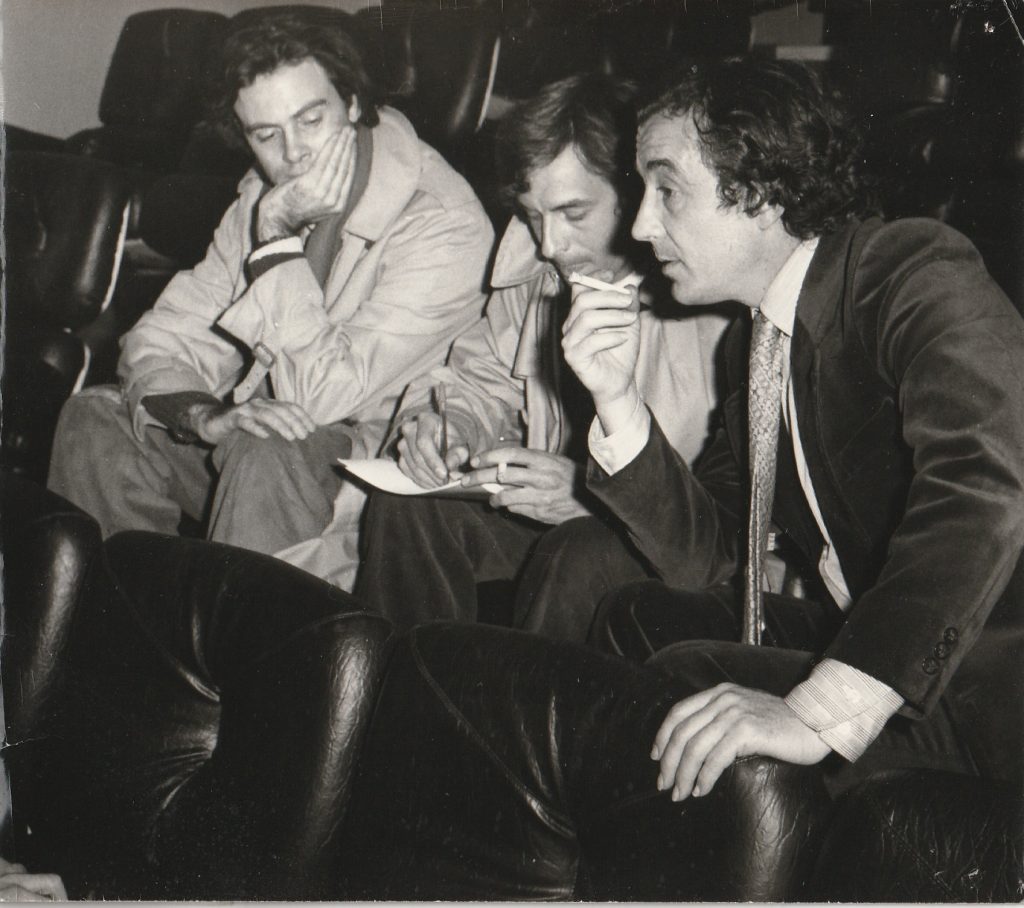

Interview de Louis Malle et Patrick Modiano. Robert Belleret. Licensed via Creative Commons.