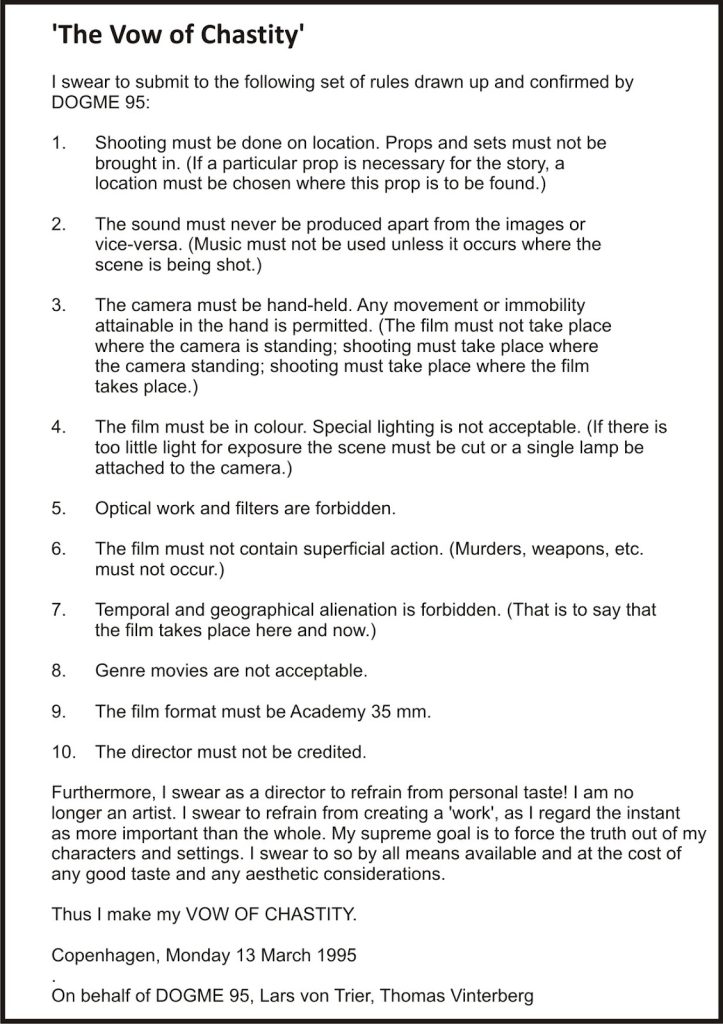

Why don’t we have film movements anymore? It’s been 30 years since Denmark’s two most bombastic directors lit a fuse that sparked the last great revolution in independent film. Both inspired by the French New Wave and rejecting many of the movement’s artistic principles, Lars von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg sought to purify cinema through a set of rules. The cheekily named Vow of Chastity (just watch von Trier’s Nymphomaniac films to get the joke) was a list of 10 simple rules for filmmakers. The biblical number surely feels intentional. As does the lack of enumeration. In reaction to the rise of CGI driven blockbusters that they (correctly) predicted would dominate movies, they advocated for an ultra-minimalist filmmaking style defined by a set of principles. The crux of these rules was simple, but stringent: use what’s available. These even went so far as to limit how productions could attain props; they had to be part of the film’s natural setting.

The ’95 Thesis

Of course, for a tongue-in-cheek group of militants trying to jumpstart a new avant garde cinema, there were naturally tensions. Despite decrying the bourgeois tendencies of auteur driven movements like the French New Wave, they were directly inspired by Francois Truffaut’s “A Certain Tendency of French Cinema”, one of the movement’s founding documents. Anxious about the democratization of film through digital technologies, Dogma 95 required directors to shoot on 35mm film. No ego driven artists, please, but also watch out for the normies with their DV camcorders.

Granted, almost every Dogma 95 film, even those by Vinterberg and von Trier, failed to rigidly follow the code. Of the rules themselves, a few dealt with the types of story and storytelling devices. No genre films like action or horror. Films must avoid “temporal or geographical alienation” to be set in the present day where the production happened. And of course, the amorphous ban on “no superficial action” like violence. The rest were more technical and logistic regulations on filming, like what film, sound, and props could be used.

Revolution Rules

In the end, Dogma 95 was a movement started by famously disingenuous provocateurs, self-conscious of their own pretension. With an arbitrarily followed set of even more arbitrary rules. That even the members would likely admit produced a mixed set of results across 35 films. And almost certainly didn’t achieve the stated goals of purifying cinema, if such a feat were even manageable. So why is the Dogma 95 dogma still relevant today?

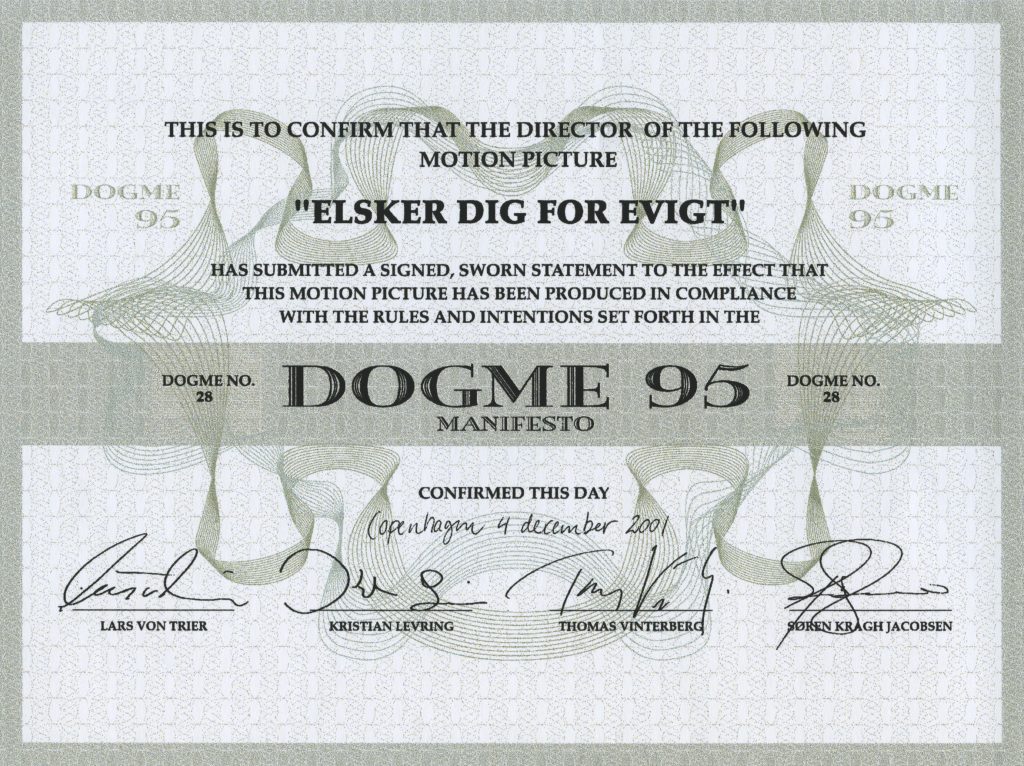

For starters, the group had an impressive output over a relatively short period of time. As technological and financial developments made it harder to shoot on film, the unaffiliated group of artists made 35 films in a dozen countries. These ranged from truly experimental works rarely screened to minor arthouse hits. They were receptive to women filmmakers before it was cool. Clearly, Vinterberg and von Trier inspired a generation of independent filmmakers. Many of these directors are still making interesting works. Hell, Vinterberg won an Oscar not that long ago.

Dogma ’25?

Making films under a set of rules may seem counterintuitive to creative freedom. However, almost all films are determined by a certain set of rules. Sometimes these are ironclad censorship laws. Sometimes they’re vague, like ratings codes and studio notes. For independent filmmakers in the USA, it’s almost always the realities dictated by funding. Behind the high-minded claims about cinema, there are also some practical elements to the codes for independent filmmakers. The idea of not only using locations that are available but tailoring a story to what the location offers is useful advice for any filmmaker without a studio expense account.

The overlooked skill of great filmmakers is their ability to channel these restrictions into art. Filmmakers working in the Soviet Union and fundamentalist Iran, for example, have made astounding works. Even directors working in contemporary Hollywood can sneak some artistry into branded pieces of IP-driven crap. The Dogma 95 movement was simply more open honest about the bullshit filmmakers have to deal with.

And for the most part, it worked. The movement died a natural death. Today, it seems nearly impossible that an avant garde group could shoot on actual film. The next wave of radical filmmakers should embrace the liberating tendencies of digital technology. At the same time, we may need a set of aesthetic and narrative principles to counteract everything else about the digital age.

Image Credits

Banner: The Idiots, Lars von Trier

“The Vows of Chastity”, Dogme 95